Blog

ONN in conversation: Yes, government funding will get easier for nonprofits – Archived Content

Funding reform, arguably one of ONN’s most challenging policy files to-date, has the network working closely with government to reform the policies, practices, and procedures for how funding is provided to the sector. Funding, cited as a key barrier facing nonprofit organizations, is not only about the size and stability of dollars, but also the administrative requirements and how the funding flows. This, for now, is the focus of ONN’s funding reform work. The next phase of discussions will include broader issues such as real costs and addressing cost-of-living increases.

We sat down with Liz Sutherland, ONN’s Policy Advisor, to give us the scoop on the Joint Funding Reform Forum (JFRF) and the changes underway to ensure a smoother funding relationship between nonprofits and the Government of Ontario.

What sparked this funding-focused table to address the relationship between the sector and the Ontario government?

You can track the roots of this back to the Open for Business process (2011-2012), essentially a call from government for industry sectors to come forward and say how “red tape” could be cut in ways that don’t require new legislation or new funding. And so the nonprofit sector got organized and put together a proposal for ways government could make life easier for nonprofits. There were other pieces to this ask (like police record checks), but funding reform took up the majority of the proposal. The point was that it was important to have a cross-government approach.

Soon after, the Joint Funding Reform Steering Committee was established, co-chaired by ONN and the Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration. But without a strong mandate to drive change across government, progress was slow.

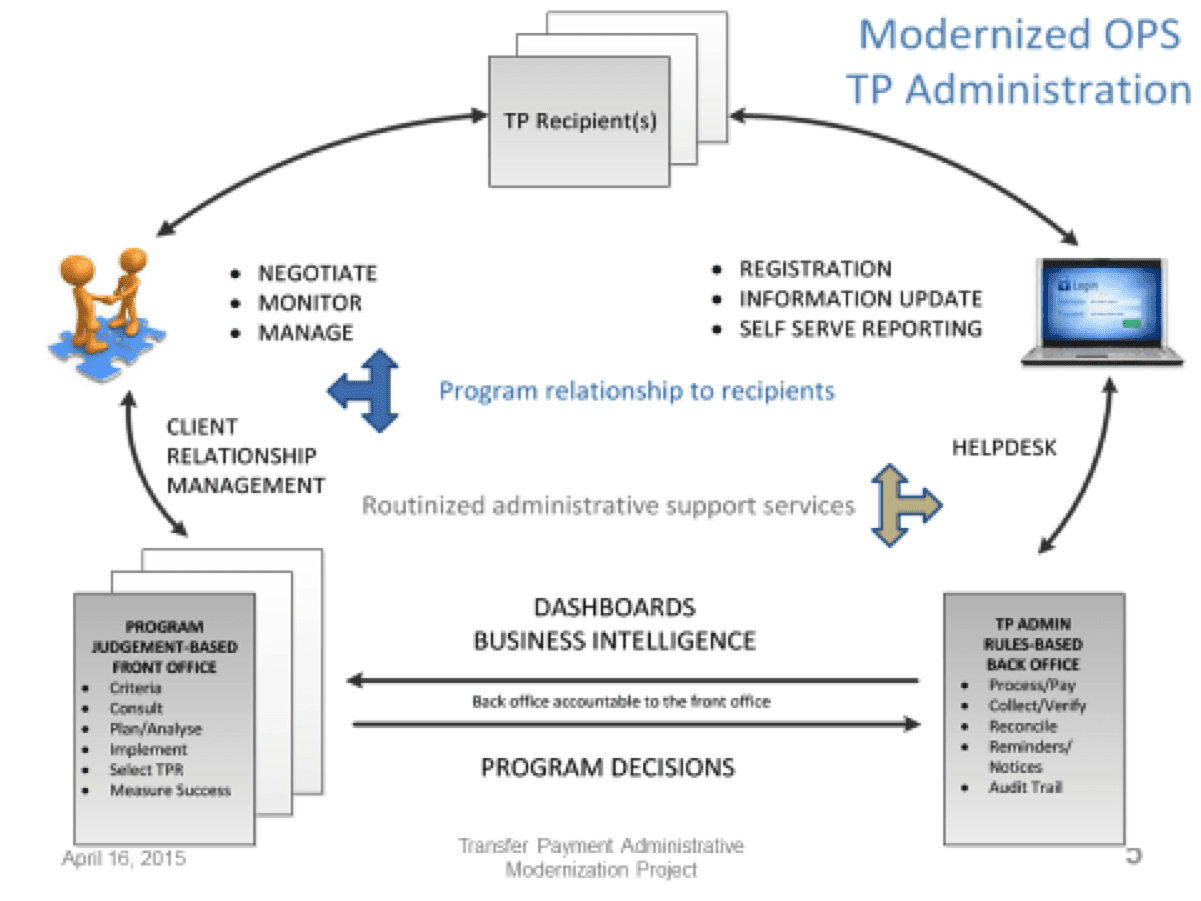

In late 2014, the Steering Committee was restructured to create the Joint Funding Reform Forum (JFRF). It has seven participants from the nonprofit sector and seven from various provincial ministries. The reporting lines were changed so that the Treasury Board Secretariat (which focuses on efficient public spending and internal management across ministries) plays a larger role in implementing the JFRF agenda. That’s when ONN developed a relationship with Treasury Board staff to modernize transfer payment agreements, called Transfer Payment Administration Modernization (TPAM). JFRF’s two-year mandate is coming to an end in December 2016.

ONN has a goal to transform the funding relationship with government by 2020. What JFRF efforts are underway?

The JFRF endorsed the Vision 2020 document that lays out where we want to be by 2020. It’s a picture of what the investment relationship between government and nonprofits should look like. It addresses everything from grant application processes and reporting requirements to partnerships of trust (instead of one-way management and accountability).

Last winter, ONN supported the TPAM office in developing Principles for Transfer Payment Administrative Modernization, co-designed with nonprofits and government. There are three guiding principles for creating transfer payment relationships: stewardship, reciprocal respect, and accountability; and three principles for administering transfer payments: simple, proportional, and flexible.

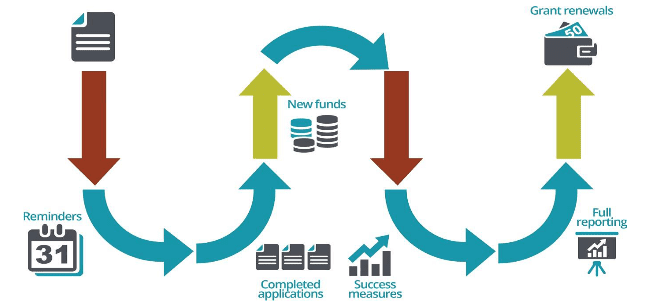

The other foundational piece is implementing “common business registration” for nonprofits using their Canada Revenue Agency business numbers. This would apply to all organizations that receive provincial government funding. Right now, nobody has a complete picture of the funded nonprofit sector, including how many nonprofits receive funding. The Ontario government has just started rolling out this common registration process. Once it’s completed, it will enable government to aggregate data in order to see, for example, how many relationships a nonprofit has with multiple ministries, or the number of nonprofits that receive funding from the government. It’s a really simple thing, but it’s going to have a profound impact on what we know about the funded nonprofit sector.

Once common registration is in place, there’s a lot that can be done, including a consolidated approach to risk management. Let’s say you’ve received funding from one ministry, and you apply for funding from another ministry. That ministry currently has no way of knowing if you’re getting funding from the first ministry, so it’s going to assign a high level of accountability and reporting. However, if it knew you were already funded by a provincial ministry and your accounting and delivery history was strong, they could rely on your nonprofit’s track record to reduce the administrative burden.

One JFRF objective is “simplified standard contracts” for organizations funded by multiple government programs. Define this for us. What would it mean for nonprofits? For government?

A standard contract would be an agreement that’s consistent over time and across ministries. You wouldn’t have to go to your legal advisor when you get a new contract the next year, and it would simplify the agreement renewal process. We’re hoping for a common budget template, using standardized lines, so you don’t have to translate too much from your own organization to budget categories across multiple ministries. It’s being tested with the Ministry of Social and Community Services and the Ministry of Children and Youth Services.

It’s been challenging to get to one standard contract though, because a lot of ministries believe they have “the” great contract. The latest thinking is that the government will never be able to reduce things to a single contract but, under the updated Transfer Payment Accountability Directive that goes into effect April 1, 2017, there will be a limited “suite” of standard contracts that most ministries and programs will start to use.

In its 2016 pre-budget submission, ONN asked for an umbrella agreement to be pilot tested with community hubs. Why community hubs and what came of this suggestion?

We know there are a lot of nonprofits that get funding from more than one provincial program and sometimes from more than one ministry. It can be a nightmare trying to manage those different contracts and, essentially, contort budget numbers to fit the rules and regulations of each ministry’s program. So, an umbrella agreement would be an overall contract with a lead ministry and, within that, there would be funding streams for different funding programs. Basically, the lead ministry would act as a liaison on the government’s side, and ideally it would manage the reporting to other programs that fund you.

Community hubs are the classic example of a multi-funding organization, because they often offer different services and typically get funds from multiple ministries. You can imagine the amount of time and effort that goes into reporting. So, if you can make this work for a community hub, you can make it work for anyone. This isn’t easy though, as community hubs often have different governance models.

The team in charge of the open government initiative at Treasury Board Secretariat ran a design lab in spring 2016 to generate and test ideas that would make funding easier for community hubs. Building on one of the recommendations from the Ontario government’s 2015 Community Hubs Advisory Panel report, the design lab developed four prototypes, one of which was for a coordinated impact agreement – a type of umbrella agreement. The prototype has been delivered to the TPAM Office for further study and development.

Grants Ontario is looking to expand its scope and improve the user experience. What changes are being proposed, and how could they reduce the administrative burden for nonprofits?

Grants Ontario is an online portal where organizations can apply for one-time funding and upload reports. It serves a number of different ministries. It had a fairly narrow scope at first, but now is broadening its offerings to more ministries. There is a commitment to have all one-time grants across government available via Grants Ontario over the next three years. The nonprofit sector has provided a lot of feedback since the Grants Ontario system was launched and the team has upgraded the system a number of times to address the glitches.

A focus group was held this past summer to address some of the key issues and Grants Ontario reported that this feedback was extremely helpful in planning their next round of system updates. In fact, Grants Ontario and ONN have decided to convene an ongoing user group that will meet twice a year to provide advice and feedback on system upgrades. This group will start meeting in January 2017.

Another objective is increased budget flexibility for organizations with a proven track record. The point is to help them be more nimble and responsive. What about budget flexibility from the modernization process?

This is a really important goal for the funding reform agenda and it’s a challenging one. The issue is acutely felt by multi-funded organizations because they have so little leeway in terms of moving money around if financial circumstances change, or if they find they have underspent on one budget line and overspent on another. It’s sometimes hard to predict what your budget will look like a year in advance. Part of the problem is that ministry budget templates focus on micro expenses so you’re not just talking about broad budget categories. I think it’s safe to say that this requires a culture shift in government because it needs to relax its controls on budget categories.

But there are precedents in place, with some ministries that use only a few (3-4) budget categories and offer the flexibility to move money or carry it forward. We need to translate this practice to other ministries. We need to emphasize that this doesn’t mean any less accountability: nonprofits still report on exactly what they spent for any given program stream.

This is about the quality of the relationship between ministries and funded nonprofits. What if a project idea is experimental or you’re reaching out to serve new groups? Especially when you’re doing more innovative things, you really need budget flexibility.

What proposed changes would affect financial and outcome reporting for nonprofits? And, how would these changes benefit nonprofit administration and evaluation?

Many nonprofits have to produce reports at the end of the year for funders, along with a specific financial audited statement for projects. This means you have to bring in an auditor on top of the audited financial statements you already produce for your organization’s board. The funder doesn’t pay for this – it’s overhead.

We’re thrilled to see that the Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres (OFIFC) has put some hard numbers on this issue. It did its own internal study and documented how much staff time and extra auditing fees it was costing the centres to do funder-specific audit reports on top of their organizational audit. They found that elimination of additional program specific reporting at year end would save $37,000 and more than 95 hours of OFIFC finance staff time.

This inspired the TPAM Office to run a pilot, testing the use of consolidated financial statements from nonprofits as a stand-alone substitute for one-off program audit reports. It’s aligned with what nonprofits produce for their boards, along with what the funder needs for its financial audited statement.

The point is for government to focus more on outcomes like program quality and meeting client needs, rather than focusing too much on monitoring activities and compliance with rules. However, outcome reporting is a tricky issue. It could be great because nonprofits can simply show the intended outcomes were met while building into their (autonomously developed) budgets the ability to sustain their missions and internal infrastructure.

Yet, some subsectors may not be ready for outcome-based reporting because the data just isn’t there. For example, in employment services, one outcome might be easy to define, like “individual gets a job.” But, in terms of serving people with developmental disabilities, how do you know what success looks like? What’s a reasonable expectation for the people you serve, given the context you live in, etc.? This will take more data and evaluation across the sector before we can adopt it.

Provided the Joint Funding Reform Forum meets its 2015-2016 goals, what could be its long-term impact on the sector?

We’d like to broaden funding reform to talk about the investment relationship as a whole – trust, stewardship as principles. Once we get rid of some of the administrative burden, what does the relationship look like? How do we work collectively to meet the needs of our community as a true partner of government, rather than as a subject of all its terms and conditions? This includes dealing with thorny issues like the fact that funding levels have not kept pace with inflation even as community needs have risen and the regulatory environment continues to impose more and more of a burden on nonprofits.

The Ontario government is focused on balancing its budget in 2017. There’s been a history of restraint within the sector and a lot of unmet needs, so now is a good time to start talking as a sector about how we can start filling gaps.

So there are two main challenges. The first is to scale up the good practices that have been piloted by the TPAM Office and its partners and roll them out across government in a coordinated way. And the second is to start to answer the difficult question about the broader investment relationship and how to address the unmet needs in our communities. At this point, we encourage nonprofits to share their stories with ONN about how they are funded and their experiences with good or bad practices. That would help us keep the agenda moving forward and make these changes mandatory across government.

Government is a big organization to turn around and the funding reform agenda entails a long and incremental process. Nonprofits may not feel the changes immediately, but we’ll keep pushing because it’s a vital sector priority.