Blog

Network Weaving 101: What your network role says about you

By: John Saunders

One key strength to network building is that anyone can do it. In fact, most of us are already weavers to different extents, even if (like me) you might feel you still have a lot to learn. Everyone can develop leadership capacities and play a vital role in network development and growth. And as the leadership capacities of members grow, so too does the power of the network.

So, how do you get to know your network? And how do you get to know your role? It’s important to understand your network not only to measure its effectiveness, but also to identify ways to improve its impact and extend its engagement with members.

I once worked with a network focused on improving Canadian work and immigration policies. People would meet and talk, but we didn’t always keep clear records of decisions or actions. Being new to this way of organizing, many of us assumed someone else was keeping track or were more interested in bigger-picture actions. In this network, I took on on specific, short-term tasks, like facilitating working meetings or taking minutes. I also connected people who had shared interests. Other people in the network focused on convening larger assemblies or delving into the details of federal legislation and sharing their clear-language interpretations.

I learned quickly that there’s work for everyone in a network – and that everyone has skills they can contribute. My role mixed project coordinator work with network connector relationship building (see more about this below).

Unlike organizations, which usually have clear and structured processes, goals and positions, networks are often more open ended and flexible. Membership can include multiple organizations, groups and individual people, representing broader communities or themselves.

Networks may emerge to address a specific issue (like coalitions or alliances), but may well continue past a particular achievement or grow to take on different challenges or opportunities.

Or they may disband entirely, once their work is done.

In the process, network building spurs meaningful relationships among members and communities.

Think of it as valuing both the process and the outcome.

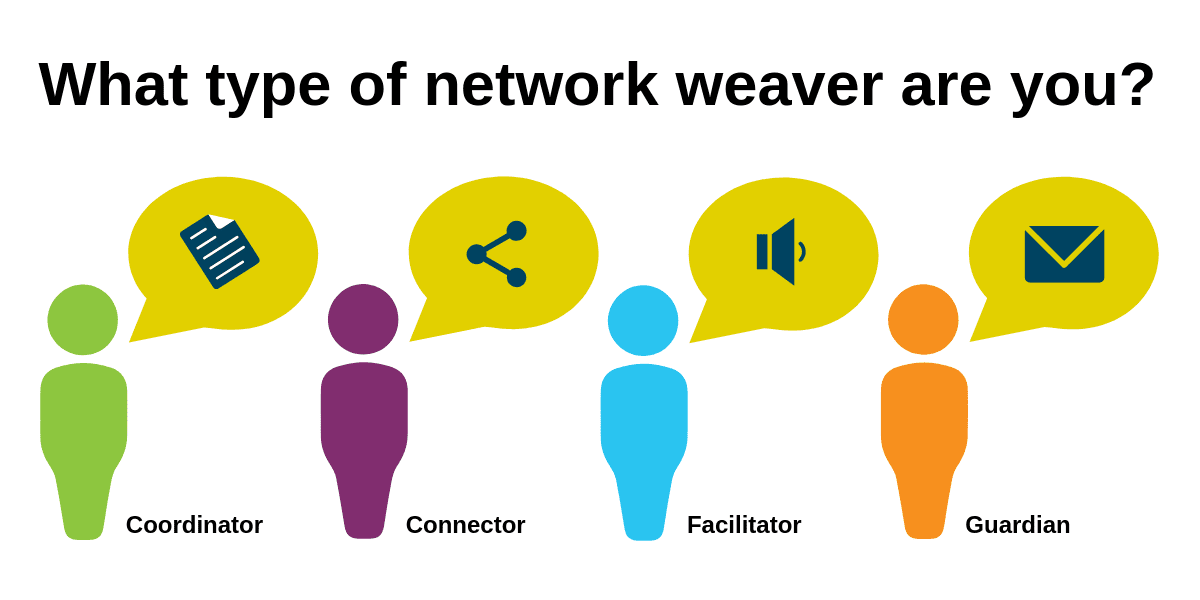

Four roles for network leaders

Network leadership can be more inclusive and open-ended than say, running a large organization or coordinating a campaign. Network leaders play to their strengths, and work collaboratively and collectively to help achieve goals. That last part is key: effective network leaders understand they are part of a web of relationships.

There are four distinct roles for network leaders:

Connectors have a good understanding of people in their networks. They can see gaps or opportunities for members to collaborate, and also help support other members as they engage. Connectors often “close the triangle”; that is, they serve as a link between two people who may not already know each other.

Project coordinators often take the lead in organizing people and tasks. They help manage the work of networks and can play a role in coaching others to do the same.

Network facilitators help convene people to address an issue or challenge. They help get the network ball rolling by gathering people or groups together and facilitating the structure or organization of the network.

Network guardians concern themselves with the well-being of the network. This can include managing communications and technical work (like setting up a web page or social media channels), finding funding opportunities, and providing training for other members.

Different from more conventional, organizational divisions of labour, networks speak more to your abilities than your job title, and give everyone an opportunity to engage and lead.

There are many checklists and resources that can help you identify your network identity. They tend to work with, or expand on, June Holley’s framework in the Network Weaving Handbook.

Four dimensions to network building

Not all networks are alike, of course, but successful ones craft a balance among priorities. Holley identifies four aspects to networks that interconnect and support each other:

Networks are intentional. They arise from people coming together on a common issue. They may have formal structures for process or membership, or may be quite open and fluid.

Networks are action-oriented in that they are trying to achieve something: policy change, community empowerment, economic development, etc. Work towards goals tends to be self-organized rather than top-down or undertaken as a single entity.

Networks are based on relationships. They work based on how they foster connection and interaction. Trust and communication are key aspects of building relationships among network members.

Networks require support. Leaders are not like bosses in organizations, and there is no HR or IT department to rely on for coordinating tasks or managing communications (like email updates or meeting agendas). As with action, support is self-organized.

Key questions to ask about your network

These four dimensions provide a good starting point for understanding how (and how well) your network works. They provide the background for asking some basic questions when you find yourself participating in a network, as part of your job, or perhaps as an interested community member:

- What are the goals of this network, and how do we know when we’ve achieved them?

- Who can be a member of the network, and how can they join?

- Who does the work?

- How well does everyone know each other, and how well do they get along?

Answering these questions should give you a clearer idea about what the network seeks to achieve and how it goes about reaching specific goals. Clearly stated goals will help members focus their attention and work, and will also make it much easier to evaluate success. Examining how work gets distributed might show whether a core group of members undertakes most tasks, while looking at roles and relationships might show if trust is shared (and shared equally) among members.

Of course, these questions are vital in determining the health and wellbeing of networks. They can also help you determine what role you yourself can play in a network.

In our next instalment, we’ll look at what we mean when we talk about network culture, and how we can build and sustain it.

John Saunders is ONN’s Communications Coordinator. He communicates with ONN members and the wider network to help the sector be a leader in decent work. He brings with him more than 20 years of experience in journalism, teaching, research and communications work. John has worked on numerous campaigns on a range of issues, including public transportation, community health, and workers’ rights.

Note: Many of the concepts and terms used in these blog posts come directly from June Holley’s Network Weaving Handbook. Many additional free resources are available from Networkweaver. For more in-depth discussions of how networks are used to influence public policy work in Canada, take a look at a recent series of articles from The Philanthropist.