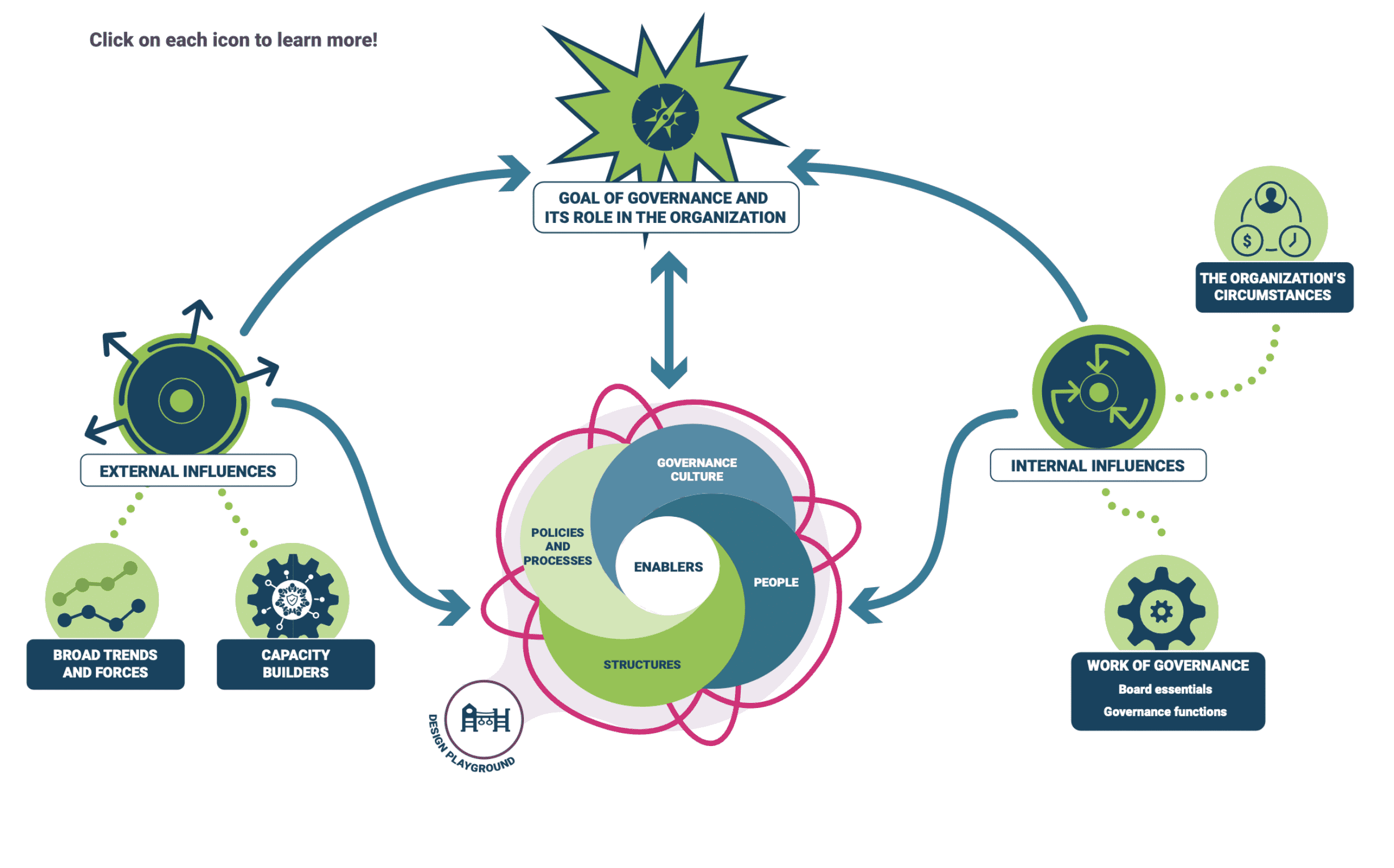

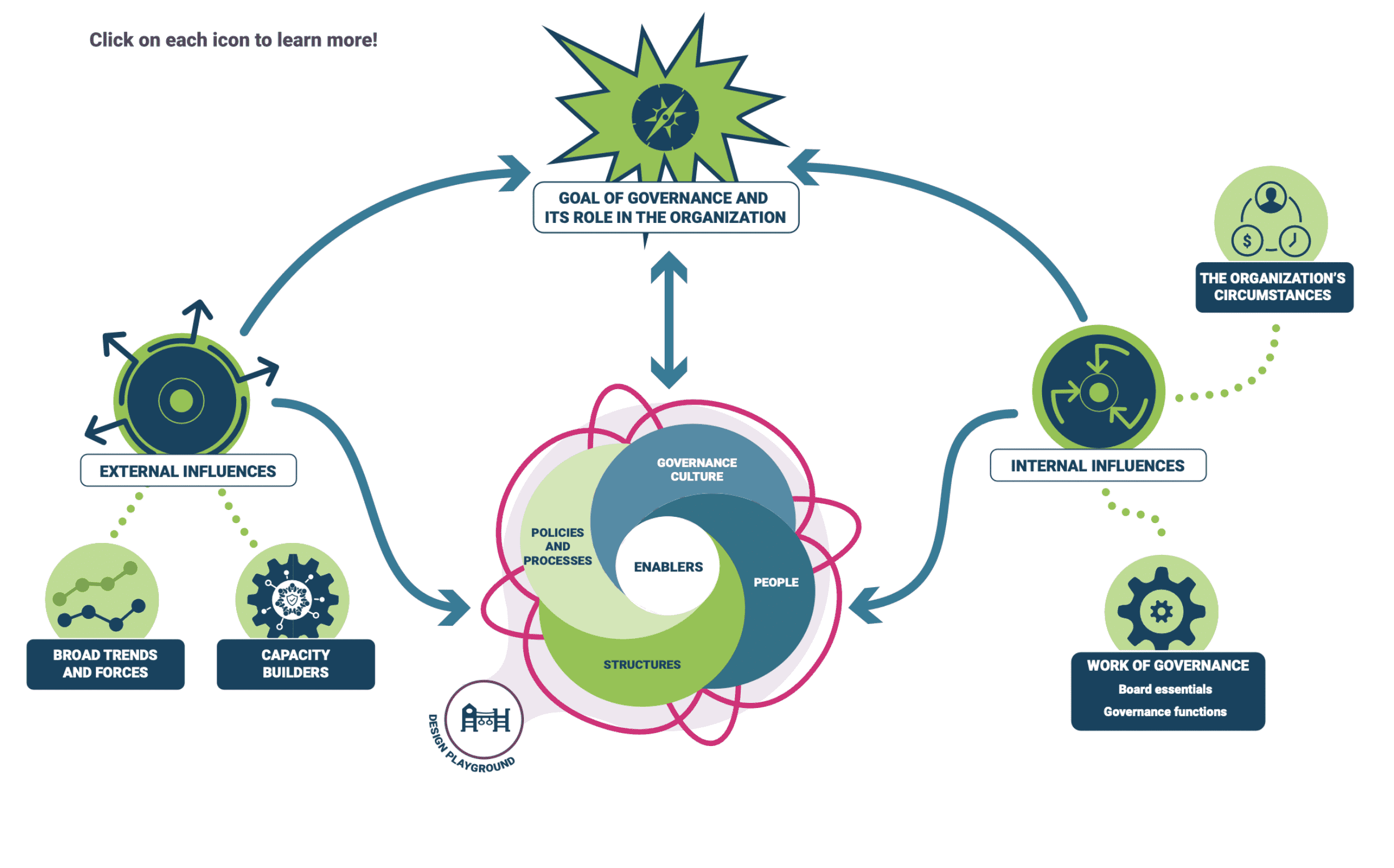

Mapping your organization’s unique governance ecosystem, from external influencers to internal enablers, creates a snapshot for board and staff leadership orientations. It can spark new ways of working and can help navigate changes in circumstances or as governance issues emerge, responding more effectively to all the interconnected parts.

Check out the ecosystem diagram below or scroll down to discover specific reasons for reimagining that you can bring to your board and staff leadership team.

Are you ready to ask braver, bolder questions about how your governance is done, and challenge age-old assumptions holding you in place? Here’s a case for change to bring to your board for a generative conversation.

1

Organizations are facing unprecedented changes in their environments and, as a result, are transforming how they operate and fulfill their mission. However, the fundamentals of governance design within nonprofit organizations haven’t changed a lot from decades ago when boards were put in place to create more accountability.

The ways that governance is designed in your organization needs to keep pace with organizational transformations, and the significant shifts in how we think about leadership. It’s more important than ever to ask bolder, braver questions about how your governance is done and who participates in it.

3

The composition of boards in nonprofit organizations needs to be more diverse. But creating more diverse boards is not enough to truly reflect the communities served and draw on a broad range of perspectives, experiences, knowledge, and skills. Organizations must rethink how people are actively engaged in decision-making beyond the board, and put equity at the core of governance culture, processes, and practices.

A key element of success is to remove real and perceived barriers, so a broad range of individuals can authentically participate in governance decision-making and help build solutions and strategies. Another is to have deep, intentional conversations about the board and staff leadership team’s collective and individual values and perspectives that might be helping or hindering participation, such as acknowledging and addressing bias, power, and privilege.

5

There are several reasons that governance design isn’t always feasible. Many board members feel the pressure to fulfill all the responsibilities of governance but are limited by the time they can contribute as volunteers. As well, boards are positioned as “ultimately responsible” for the organization, yet they can never have the same knowledge of the organization’s environment and issues as the staff. At the same time, many CEO/ED’s report stress and burnout with the challenges of mobilizing and supporting the board.

Another reason organizations struggle is that just one negative variable can derail good governance, such as the personality and skills of the board chair, the ability to recruit the right people, and the relationship between the board and CEO/ED.

Creating a more feasible governance system isn’t an easy fix. It means grappling with complex questions and the tensions inherent to them. For example, what are realistic expectations of the board, and how can you augment their skills, knowledge, and experience with a broader network of people, without it becoming burdensome? What if the board played more of the role of “host” of governance, and less the “home” of governance? How can the board and staff leadership better partner in the work of governance, while keeping the board out of operations?

2

The work of governance has gotten tougher and more complicated. There are increased demands on board members and staff leadership to govern well. The mix of required knowledge, skills, and experience is more complex, and the growth of system-wide collaborations makes it even more challenging. It’s not surprising that many organizations report difficulties in creating governance that works for them.

Viewing governance as a dynamic ecosystem, that is much more than just board performance, can help unravel the complexities. This more expansive lens encourages your organization to envision governance as a web of interconnected parts. For example, if your circumstances change, such as a significant shift in the organization’s purpose, stakeholders, financing, or program directions, then it should prompt a review of your governance culture, processes, structures, and people. You can’t make a change in one, without impacting another. For example, if you tighten your risk management checks and balances, it may stifle innovation. You may put the perfect structure in place, but it won’t work if people aren’t engaged effectively.

Every organization’s ecosystem is unique; there’s no ideal model or set of practices that works for everyone. Organizations need to create custom-built designs and solutions.

4

Governance design isn’t evolving to meet the expectations of emerging leaders. The Next Generation Governance research found that many emerging leaders see governance work as demanding, with onerous and complex accountabilities in an environment of underfunding and restricted capacity to innovate. If they’re interested in making a difference, there are attractive alternatives, such as social enterprises, corporate cause work, or entrepreneurial ventures. At the same time, there is a shortage of leadership volunteers to fill governance roles because the smaller Gen X group can’t replace the larger cohort of baby boomers as they exit.

Your organization’s governance design can be reimagined to meet these challenges. For example, you can create different kinds of governance leadership opportunities beyond sitting on the board and rethink how to conduct meetings and make decisions.

6

The way that governance is done can get stuck in place because of a misconception that there aren’t many choices. While there are binding legislative and legal rules that must be met, there’s more room for innovations in governance than many people believe. For example, organizations can design their own structures and processes based on their unique circumstances and many governance responsibilities can be delegated and shared.

Habits, norms and assumptions can also be misconstrued as fixed but are actually fluid. For example, a governance structure, like a council, may have been created as a mechanism for stakeholder engagement but no longer makes sense given the shift to more agile ways of working. In other instances, personal preferences might become entrenched practices, but they can be revamped.

There are many opportunities for reimagining your governance so it’s better positioned for your current and future environment. The journey can start by exploring what’s holding it in place.

1

Organizations are facing unprecedented changes in their environments and, as a result, are transforming how they operate and fulfill their mission. However, the fundamentals of governance design within nonprofit organizations haven’t changed a lot from decades ago when boards were put in place to create more accountability.

The ways that governance is designed in your organization needs to keep pace with organizational transformations, and the significant shifts in how we think about leadership. It’s more important than ever to ask bolder, braver questions about how your governance is done and who participates in it.

2

The work of governance has gotten tougher and more complicated. There are increased demands on board members and staff leadership to govern well. The mix of required knowledge, skills, and experience is more complex, and the growth of system-wide collaborations makes it even more challenging. It’s not surprising that many organizations report difficulties in creating governance that works for them.

Viewing governance as a dynamic ecosystem, that is much more than just board performance, can help unravel the complexities. This more expansive lens encourages your organization to envision governance as a web of interconnected parts. For example, if your circumstances change, such as a significant shift in the organization’s purpose, stakeholders, financing, or program directions, then it should prompt a review of your governance culture, processes, structures, and people. You can’t make a change in one, without impacting another. For example, if you tighten your risk management checks and balances, it may stifle innovation. You may put the perfect structure in place, but it won’t work if people aren’t engaged effectively.

Every organization’s ecosystem is unique; there’s no ideal model or set of practices that works for everyone. Organizations need to create custom-built designs and solutions.

3

The composition of boards in nonprofit organizations needs to be more diverse. But creating more diverse boards is not enough to truly reflect the communities served and draw on a broad range of perspectives, experiences, knowledge, and skills. Organizations must rethink how people are actively engaged in decision-making beyond the board, and put equity at the core of governance culture, processes, and practices.

A key element of success is to remove real and perceived barriers, so a broad range of individuals can authentically participate in governance decision-making and help build solutions and strategies. Another is to have deep, intentional conversations about the board and staff leadership team’s collective and individual values and perspectives that might be helping or hindering participation, such as acknowledging and addressing bias, power, and privilege.

4

Governance design isn’t evolving to meet the expectations of emerging leaders. The Next Generation Governance research found that many emerging leaders see governance work as demanding, with onerous and complex accountabilities in an environment of underfunding and restricted capacity to innovate. If they’re interested in making a difference, there are attractive alternatives, such as social enterprises, corporate cause work, or entrepreneurial ventures. At the same time, there is a shortage of leadership volunteers to fill governance roles because the smaller Gen X group can’t replace the larger cohort of baby boomers as they exit.

Your organization’s governance design can be reimagined to meet these challenges. For example, you can create different kinds of governance leadership opportunities beyond sitting on the board and rethink how to conduct meetings and make decisions.

5

There are several reasons that governance design isn’t always feasible. Many board members feel the pressure to fulfill all the responsibilities of governance but are limited by the time they can contribute as volunteers. As well, boards are positioned as “ultimately responsible” for the organization, yet they can never have the same knowledge of the organization’s environment and issues as the staff. At the same time, many CEO/ED’s report stress and burnout with the challenges of mobilizing and supporting the board.

Another reason organizations struggle is that just one negative variable can derail good governance, such as the personality and skills of the board chair, the ability to recruit the right people, and the relationship between the board and CEO/ED.

Creating a more feasible governance system isn’t an easy fix. It means grappling with complex questions and the tensions inherent to them. For example, what are realistic expectations of the board, and how can you augment their skills, knowledge, and experience with a broader network of people, without it becoming burdensome? What if the board played more of the role of “host” of governance, and less the “home” of governance? How can the board and staff leadership better partner in the work of governance, while keeping the board out of operations?

6

The way that governance is done can get stuck in place because of a misconception that there aren’t many choices. While there are binding legislative and legal rules that must be met, there’s more room for innovations in governance than many people believe. For example, organizations can design their own structures and processes based on their unique circumstances and many governance responsibilities can be delegated and shared.

Habits, norms and assumptions can also be misconstrued as fixed but are actually fluid. For example, a governance structure, like a council, may have been created as a mechanism for stakeholder engagement but no longer makes sense given the shift to more agile ways of working. In other instances, personal preferences might become entrenched practices, but they can be revamped.

There are many opportunities for reimagining your governance so it’s better positioned for your current and future environment. The journey can start by exploring what’s holding it in place.